Assistant Coroner Crispin Oliver today read out his judgement in the inquest of 31 year old Myles Scriven who died of a pulmonary embolism on April 16 2023 at Huddersfield Royal Infirmary. The full judgement can be read here: https://www.georgejulian.co.uk/2025/07/11/myless-inquest-coroners-conclusion/

This fifteen page judgement is an excoriating and devastating read. The coroner’s meticulous engagement with the evidence (which included witness statements and spoken evidence, hospital and GP medical records going back two years before Myles died, four expert witness reports and the recordings of earlier parts of the inquest) is clear. The judgement reads like an intensely plotted narrative with every word underpinned by evidence sources, the workings out carefully documented. It ends with an unexpected and beautifully sharp twist.

It is also a refreshing read, shot through with common sense and hints of incredulity. Myles should not have died, he experienced a bewildering set of failings across primary and secondary healthcare despite the active interventions of a loving family which includes a senior medic.

The coroner discusses how deaths from natural causes can be made unnatural, reminding me of the defence barrister at Connor’s inquest arguing drowning was a natural cause of death. The Oxford coroner sharply rebuked this argument and while largely fair, lacked the understanding Crispin Oliver demonstrated. His understanding was in part due to the commissioning of an expert witness report from learning disability expert Dr Liz Herrievan which offered incontrovertible evidence of the numerous failings. Having an expert witness in autism and learning disability is so obvious, I’m still pondering why it is not done as standard practice. We recently published a paper discussing how the ignorance of coroners can contribute to the harms generated by coronial processes for families, as well as obstruct accountability. Getting an expert in this area is a superb workaround leading to more robust engagement and arguably a knock on effect on outcomes.

Like many of the inquests covered by George Julian, the facts in Myles’ case offer an extraordinary array of failings; blood thinning medication was clearly not working and yet the consultant refused to switch to warfarin, an ECG was performed but the results not communicated to anyone leading to a lack of a follow up appointment and review three months later. The discharge letter from the hospital was “borderline useless”. By this time, despite Myles’ obvious deterioration in health, a phone call with the GP led to a note of ‘sounded ok on the phone’ on his file and an appointment three days later resulted in the incomplete recording of medical notes and safety netting advice. Myles died three weeks later.

What the coroner lays out in this judgement is a) the knowledge about Myles communicated to the hospital by his family (take time, don’t use long words or jargon, listen to the family, etc etc etc) and b) the absence of any engagement with this knowledge by professionals. This can only be wilful. The coroner reported a sense of disbelief earlier in the inquest that the hospital had in place all the necessary adjustment mechanisms, including a learning disability nurse and ongoing training, and yet none of this had any impact on the care Myles received. The lack of a hospital passport was flagged as problematic, though given the (non) actions of most professionals around Myles, I’m not sure they’d have even noticed it through their disinterested and disconnected lenses.

The coroner noted that these adjustments were essential to Myles’ care and should have been followed to the letter. Of course they should. As they should in the case of any autistic person or person with learning disabilities. And yet they aren’t. “The evidence is that this did not happen at any point in the timeline of events”. How is it possible for none of these standards to be adhered to? Again, returning to George’s inquest coverage, how many other deaths were due to failings in the most basic standards of care?

The coroner states “GPs demonstrated in their evidence that they had very little real grasp of the technical and regulatory requirements” in connection to patients with learning disabilities. Two GP’s who gave evidence did not understand what the Learning Disabilities register was or how it worked. I’m reminded of a study which found GPs didn’t know what the flag was or where to find it. Extraordinary ignorance that you think would be remedied by implicated professionals hastily with some mortification. But no. This is all apparently fine.

[Myles’ death was of so little consequence to the GPs they did not instruct legal representation until forcefully told they should by the coroner.]

In a gruelling paragraph, the coroner described how he’d come to the conclusion that the GP surgery was so woeful in practice that the character of neglect was not present; neglect can only be considered if the person obviously presents as ill. Drs Clownster and Clownstar were too clueless to notice.

I had to read the final pages of the judgement a few times as the coroner’s narrative arc is blistering. Myles died of a pulmonary embolism. The lack of adjustments made in relation to his learning disabilities resulted in incorrect decision making contributing to his death. I question the coroner’s use of ‘incorrect decision making’ here. The Dr who refused to change the medication that clearly wasn’t working couldn’t really account for this ‘decision’ saying he thought Myles had compliance issues around medication. This strikes me as more of a post-hoc rationalisation. The character of medical decision-making seems to involve more gravitas than simply not bothering to do something or ever following it up.

A Prevention of Future Deaths (PFD) Report was unsurprisingly issued to the GP surgery. In relation to the NHS Trust, there was the usual bullshit about changes implemented since Myles died which generated more words for the continually overflowing learning pot. And then the coroner smacks the judgement out of the park by issuing a second PFD to the Trust:

Tell me how best practice is going to be complied with and by when.

Wow. Yes. Please do. Adjustments (including mandatory training) simply don’t work. Ticking the box is a pointless and dangerous distraction.

I hope this judgement is read by other coroners as well as health (and absent social care) professionals. Myles was let down so blinking badly the report is a devastating, important, even groundbreaking read. Yet another much loved young person treated as disposable by health and social care professionals. Crispin Oliver, however, showed him and his family much respect, listened to their consistent and informed interventions and questions thoughtfully, and shed light on the absurdities woven through our supposedly universal healthcare system.

Thank you.

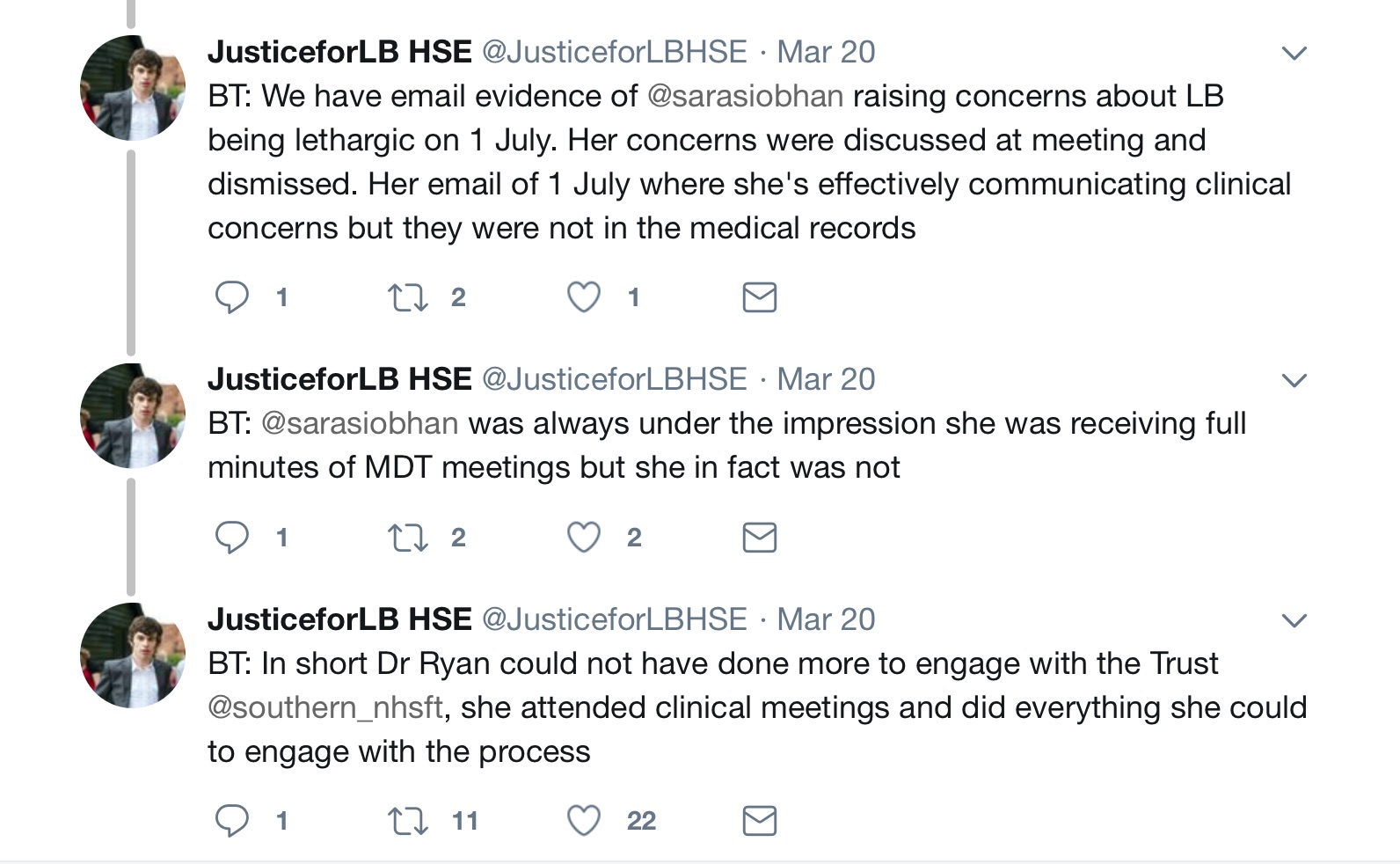

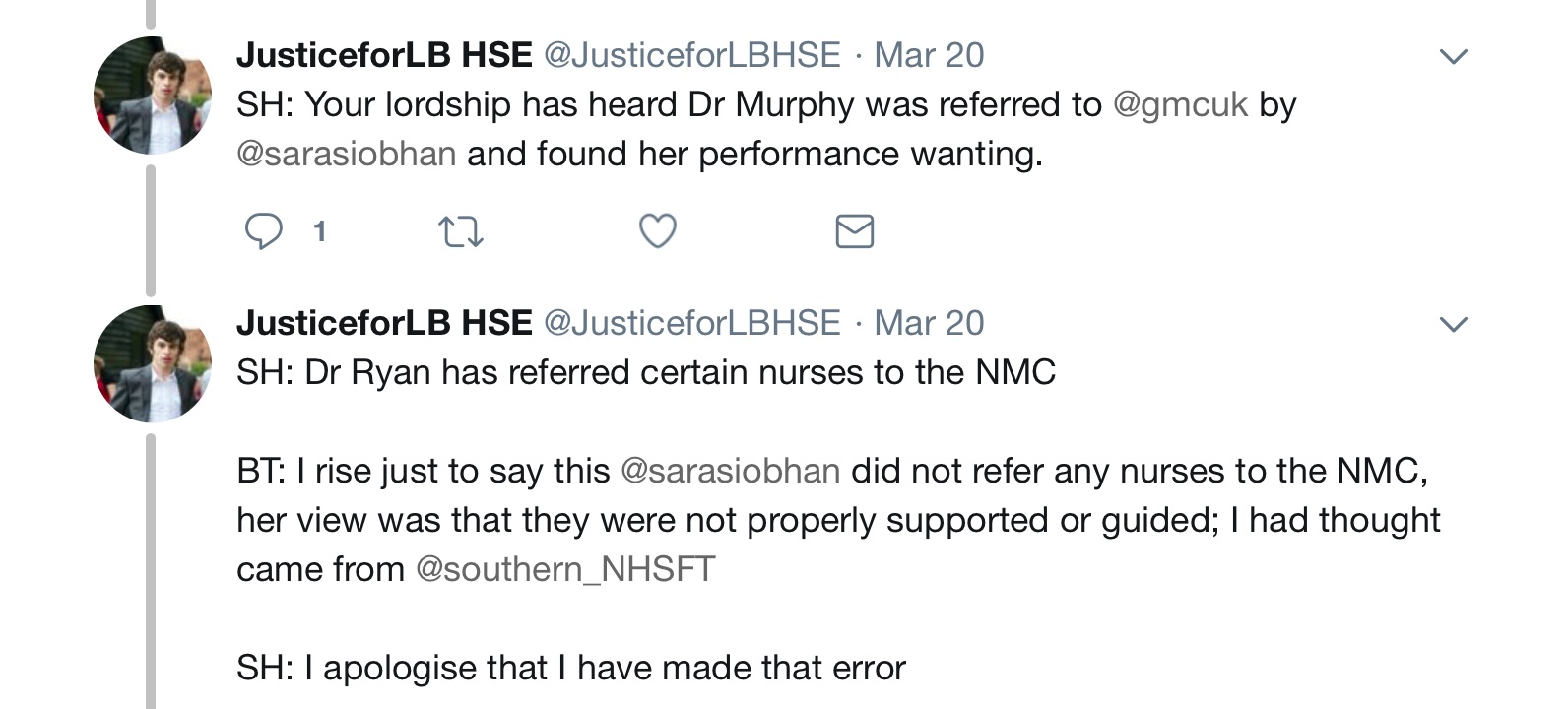

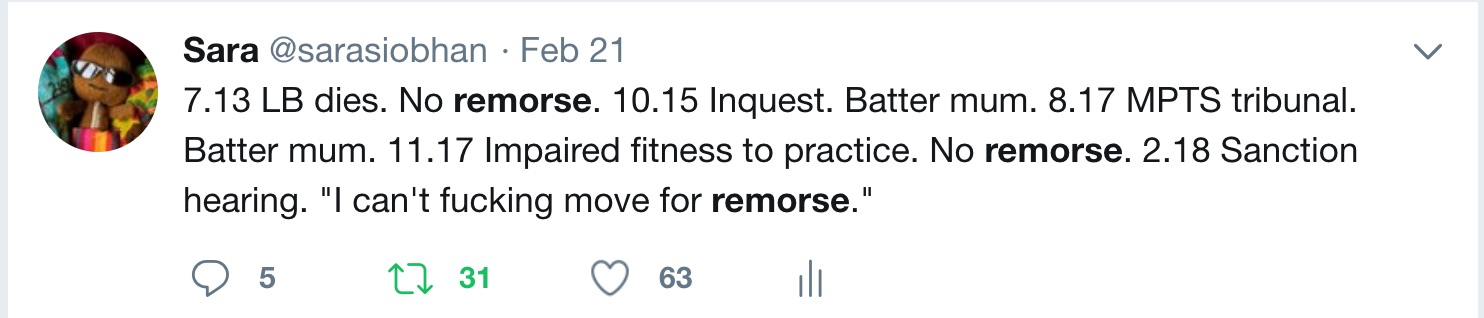

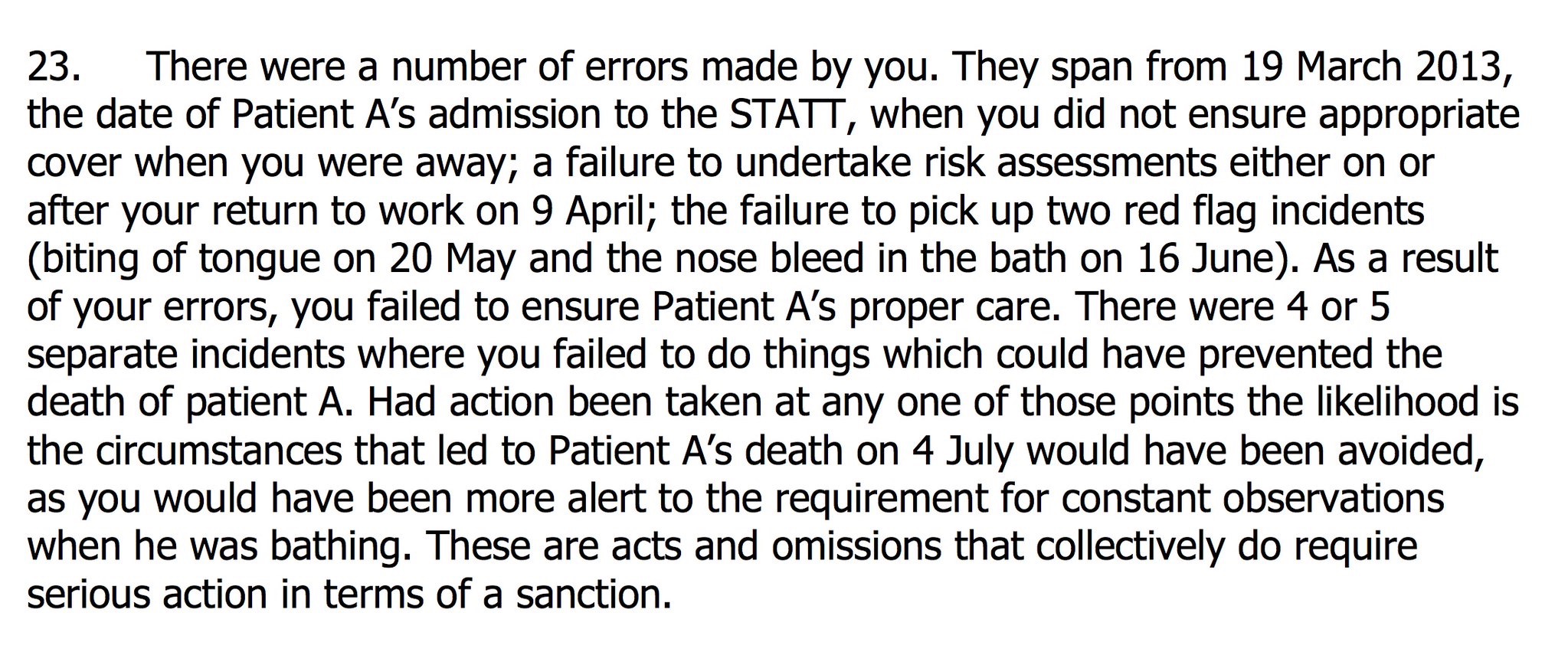

The sentencing hearing for the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) prosecution took place this week. The #JusticeforLB bus made a surprise appearance at Oxford Crown Court thanks to

The sentencing hearing for the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) prosecution took place this week. The #JusticeforLB bus made a surprise appearance at Oxford Crown Court thanks to