Babies of Rosie’s childhood friends are due. An anticipatory space rehearsed first, second, third hand. Labour. The stuff of fear, joy, anticipation, dread, sometimes devastation, pain, fear, joy. And happiness

I absorb updates, crochet. There’s always crochet.

Babies were a feature at the recent disability studies conference in Rekyavik. An unexpected and positive addition alongside the currently small number of self-advocates and family carers.

Sadness and such joy. New life, impossible sweetness, smells and the gentle warmth of the softness of the softest skin.

I feel sad at how passively and comprehensively we were ejected from the baby manual/mainstream baby gig back in the day. An ignorance that led to us tumbling into a black hole of fear and bewilderment after our GP, lab technicians and others decided a sample of Connor’s blood was indicative of a problem that curtailed his right to be considered human.

I walked him in his pushchair from the GP surgery across the park to the hospital that day to drop off the sample I’d pushed for. I didn’t know this was a first task in a role I was acquiring without realising. A role characterised by staunch advocacy and activism, contradiction, ambiguity, invisibility, blame and a consistent lack of anything outside of family life resembling the word ‘care’.

Connor was pronounced dead at the same hospital sixteen years later. I pitched up in a taxi from town that day. With Caroline, our administrator who had a daughter in her 50s with learning disabilities. Another carer.

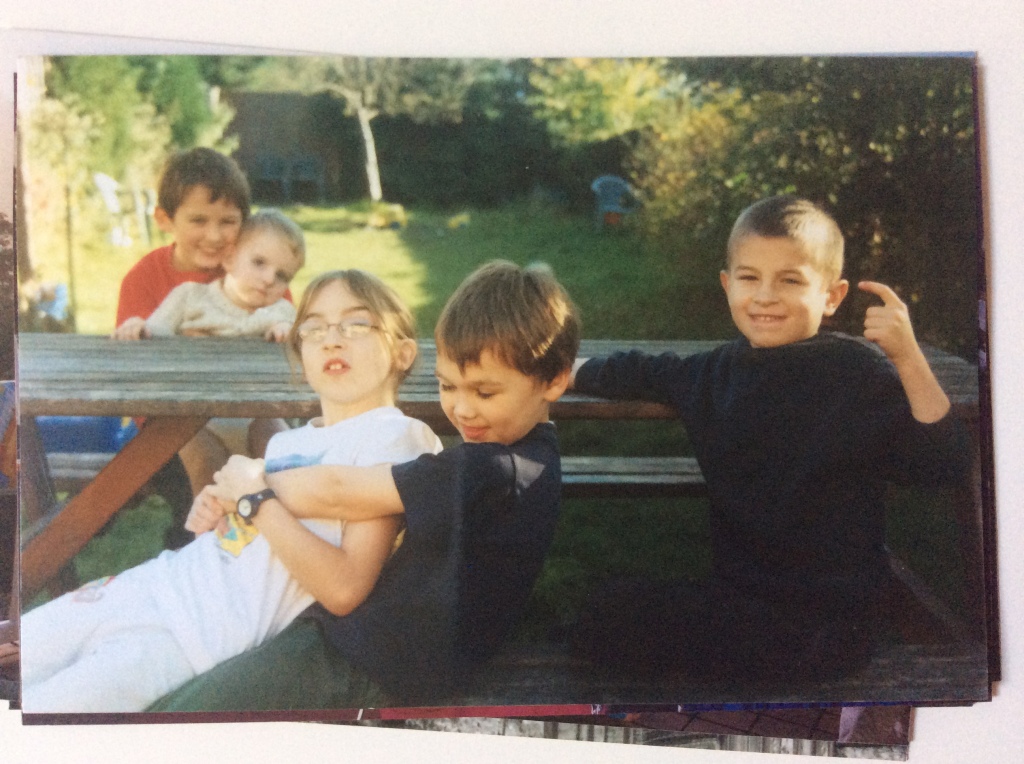

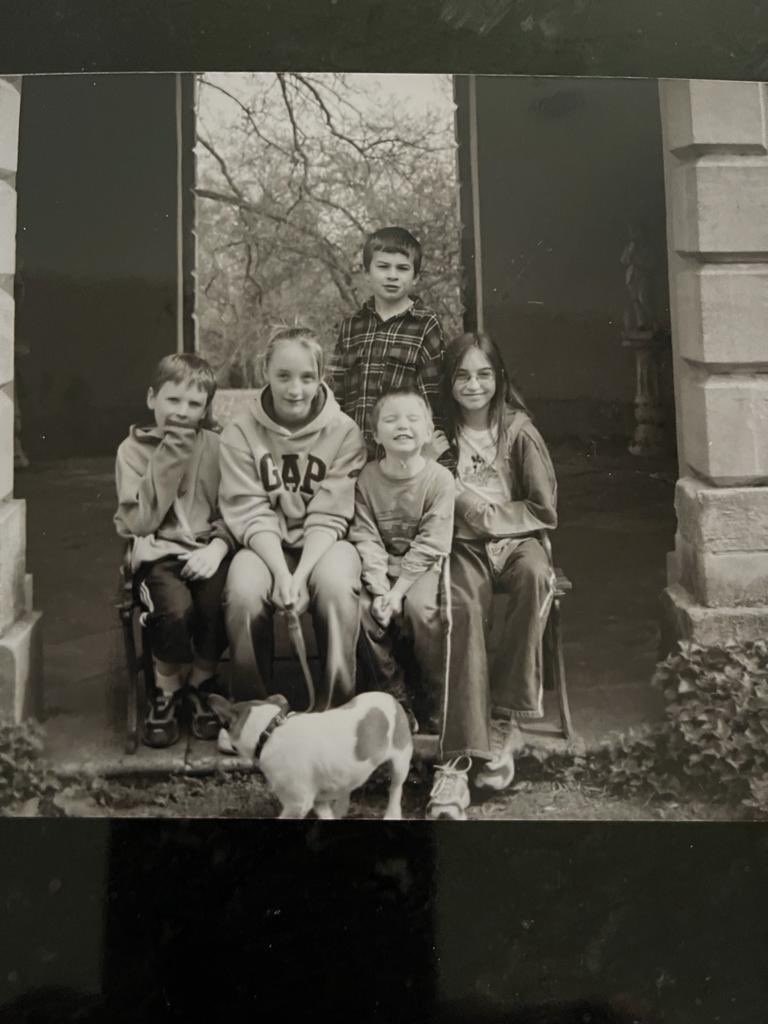

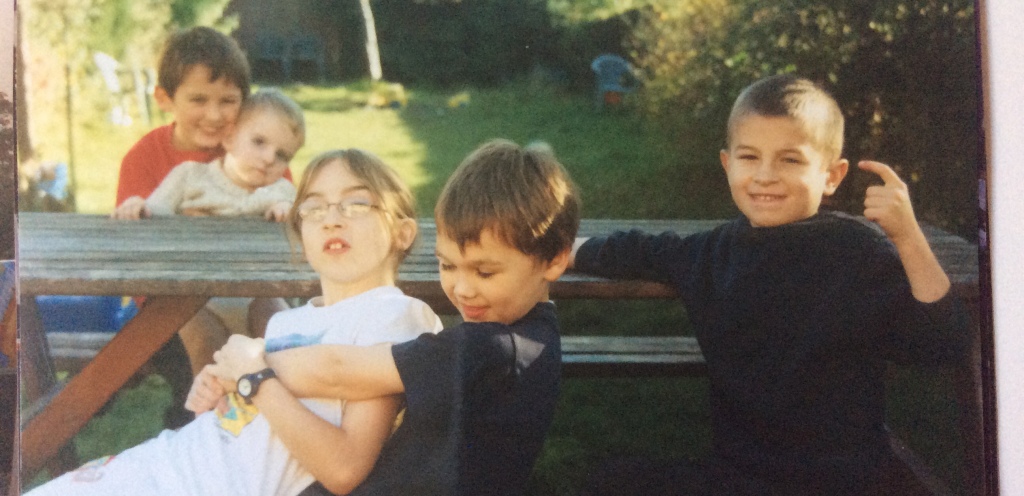

Those sixteen years had led to a savviness of sorts, of finding safe spaces. A made up (fuck you) manual, family, bunch of mates and likeminded allies of teaching assistants, teachers, occasional social and healthcare professionals.

I wish now I’d said ‘Don’t fucking diss my beautiful boy’ and swiped away the doubters without a backwards look. We had a lifetime of joy, love and laughter despite the bleak terrain.

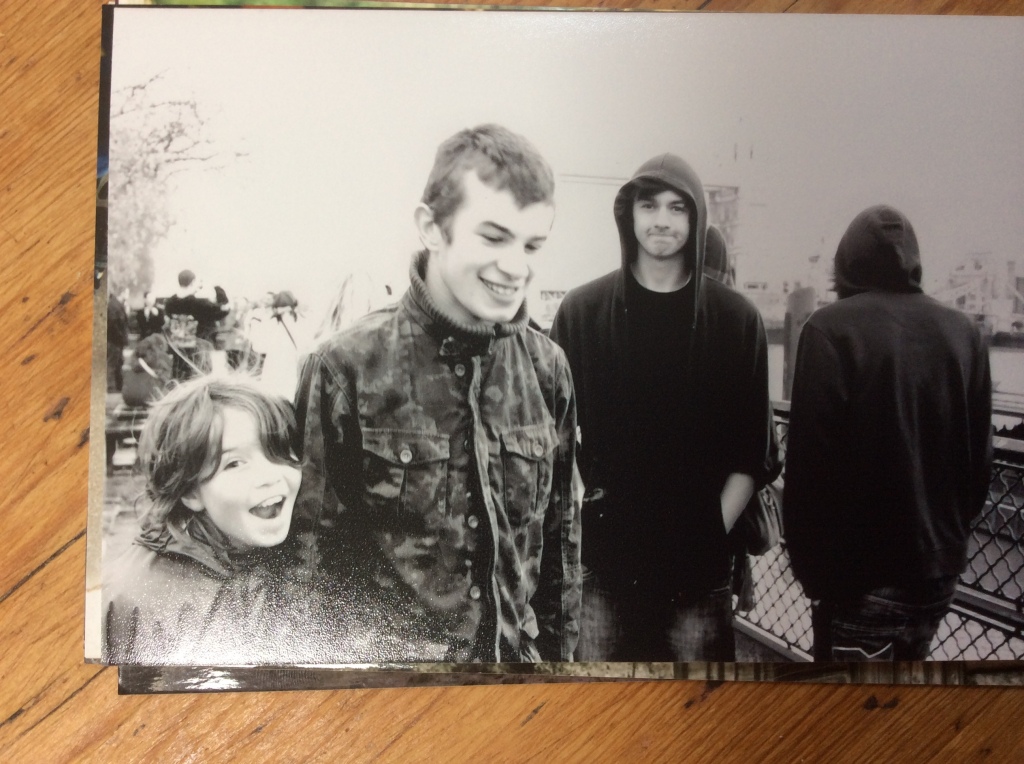

I think about our children and their partners. None of them met Connor. Jack almost did, house sharing with Rosie as students in Manchester before they got together. One of Rosie’s oldest mates Molly is expecting a baby any day with her partner she met at the same house in Manchester. H, born three weeks before Rosie and another lifelong friend had a baby today, hours before her younger sister M got married.

M and Connor pledged to marry if they were both single at 30.

New lives, joy and utter, utter sweetness. With the ever present, largely contained, sadness.