Last night LDN Charity organised an event ‘Spotlight on the abuse of people with learning disabilities’ at the London Canal Museum. The panel, chaired by Simon Jarrett, consisted of Alexis Quinn, George Julian, Amanda Topps and me. Contributions from the audience were as powerful as the panel presentations and the sense of anger and commitment to change in the packed room was palpable. This is what I said:

Last week was the 10-year anniversary of our son Connor’s death in an NHS run ATU. He drowned in the bath while staff did an online Tesco order in the office next door. Ten years has allowed time to think about what unfolded and why, and in doing so different aspects have become more prominent.

Given we each have 10 minutes to talk it seemed appropriate to produce 10 points of reflection about what happened to Connor (and others) and to think about what the lack of any real shift in the use of ATUs means.

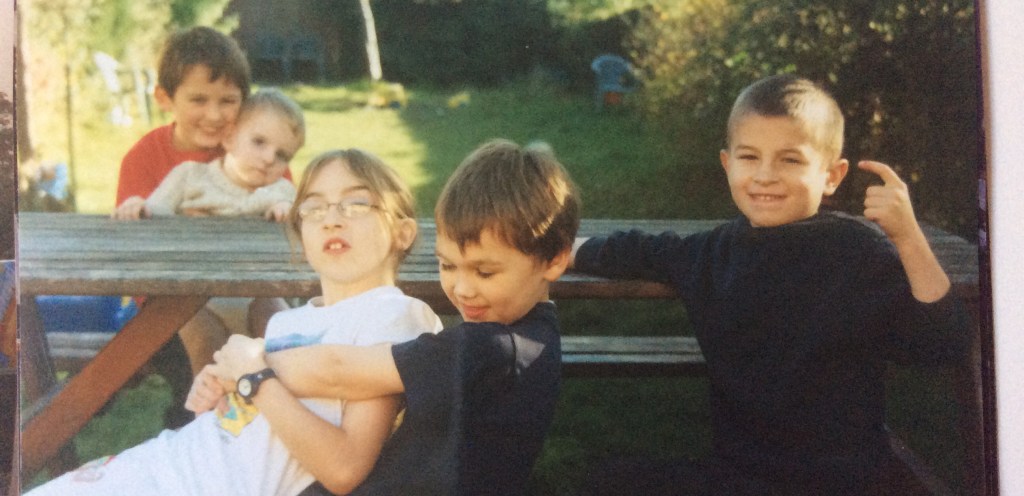

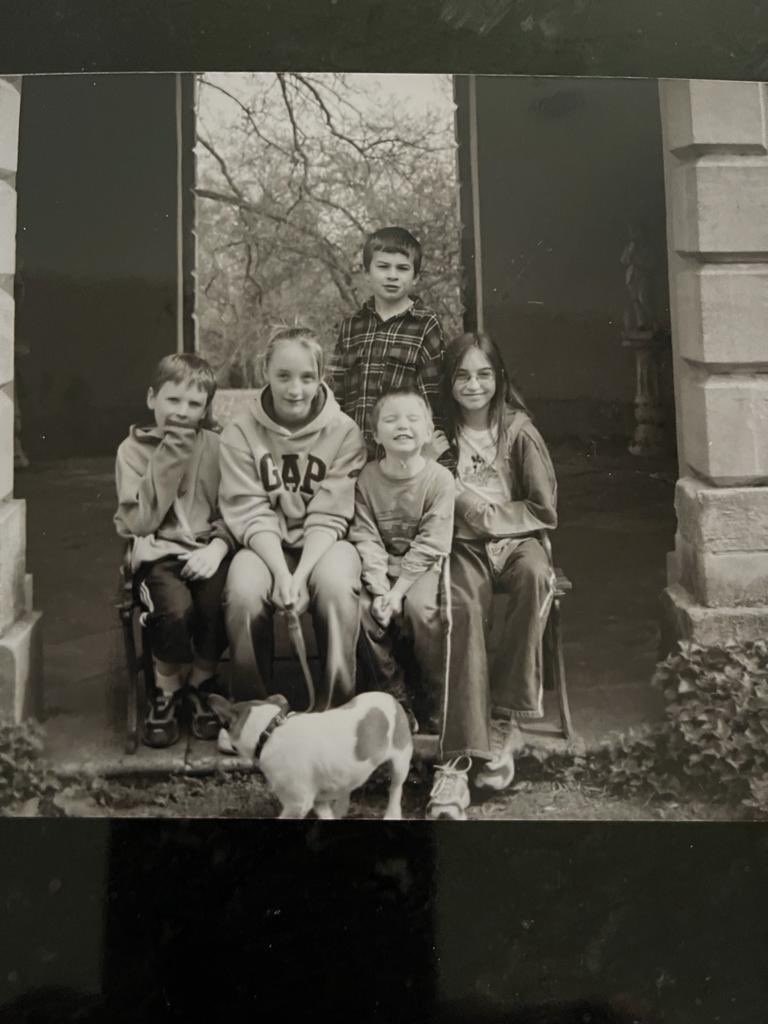

ONE. Connor was a beautiful, much loved, funny, talented and wonderfully complicated young man. He loved deeply and contributed so much to our family (and wider) that we are left with a chasm in our lives and hearts so full of love I can sometimes barely breathe.

TWO. The day we had Connor admitted to the assessment and treatment unit (ATU) a mile or so from where we lived, I didn’t know Winterbourne View was an ATU. I didn’t know what an ATU was. I thought we were taking Connor to a specialist NHS hospital unit that would be staffed by uniformed and identifiable health professionals for a few weeks to understand why he had become so distressed and unpredictable. Connor had loved visiting his grandad at the JR hospital just weeks earlier. The locum medic who came to our home to assess Connor beforehand even said there would be a ward round that evening.

I’m not sure what this not knowing, this ignorance means still. There was so much we didn’t know then. And so much people don’t know now.

THREE. Connor was admitted on a Tuesday evening. The responsible clinician whose office was in a building across the car park from the unit, didn’t bother to walk across and see him the next day. Wednesday. Or on the Thursday or Friday. On Saturday, she went off on holiday for two weeks. Again, we had no idea. There was no ward round, no crisis specialist intervention, no urgency, information, interest. No nothing. Just our boy catapulted from his family home into a space that defies words.

And this was apparently fine.

FOUR. We met the lead paramedic who responded to the call that hot, sunny July morning before we moved from Oxford in May 2021. He was a friend of a friend of one of our children and asked to meet us. He said the ambulance overshot the turn for the unit that morning, There was no one outside directing it in. When they got to the unit, the door was locked and someone was painting the outside windows. He was bewildered by this lack of urgency and the absence of information from those present. He said his team had nothing to work with, nothing to base their treatment decisions on. The unit staff were literally clueless and said nothing. There is no pretence of healthcare, death care or any care in these places.

And this is apparently fine.

FIVE. After 2 years of health and local authority records being disclosed and 4 pre-inquest hearings Connor’s inquest was unexpectedly halted in the second week in October 2015. The responsible clinician’s barrister produced evidence that a patient, Henry, had died in the same bath a few years earlier. Photographs of the bathroom taken after Henry’s death were shared with us. Some of the same staff were on duty the day Henry died. The lack of disclosing Henry’s death for over two years is extraordinary. A second psychiatrist, present the day Connor died, looked at Henry and told the coroner by phone he died of natural causes. There was no postmortem and no inquest.

When Connor’s inquest ended the coroner asked for Henry’s death to be investigated and the police took witness accounts from those present. The student nurse who was with Henry said he was told to leave the bathroom by professional X before the ambulance arrived. Professional X said he arrived at the unit after the ambulance. The coroner said it was long ago and there were bound to be contradictions. He dismissed Henry’s death again.

And this is apparently fine.

SIX. A death review commissioned by NHS England on our request was conducted by an international consultancy firm Mazars led by Marie Ann Bruce. It found only 2 out of 327 unexpected deaths of people with learning disabilities in the NHS Trust between 2011-2015 were investigated. Providing unassailable evidence you can punt human rights, regulatory procedures and processes off the nearest bridge when people with learning disabilities are involved.

SEVEN. We don’t know how many people have died in assessment and treatment units. A Dispatches film by Alison Millar ‘Under Lock and Key’ shown in 2017 included the story of Bill who died in 2011. His parents then in their 70s were given what they called ‘blood money’ after an inquest found he died as an outcome of neglect.

An early morning round table meeting was organised at Channel 4 the morning after the documentary was aired. An expectation that there would be an outcry Winterbourne View styley. No one really cared. We were coasting downwards by then, slowly and carefully unmaking scandals. I sat next to Bill’s parents who were pretty quiet. I wonder what they were thinking of this early morning shindig in central London that turned to nothing. Other than further evidence of bridge punting.

EIGHT. There is no doubt that these places deprive people of their freedoms and rights. This deprivation manifests in myriad ways from being restrained, over medicated or secluded to being denied the basic opportunities to walk in nature, experience the wind on your face or have a drink with a mate. Abuse, disrespect and devaluing profoundly erode wellbeing. We know this. Wiseman and Watson (2021) have written about the complex forms of violence experienced by people with learning disabilities and how these are critical to understanding the significant inequalities in health and wellbeing experienced by this group. And yet the numbers of those incarcerated in these places remain the same.

NINE. The unmaking of this scandal, the greedy and self-interested actors that have jostled to drink at the fountain of self-serving opportunities and nosh on the plates of croissant crumbs, to line their pockets, seize media opportunities is grotesque. The stuffing of laminated photos of dead loved ones into the hands of bereaved and battered families… There has been no auditing of the money spent, contracts doshed out, time wasted, or individuals rewarded for no success.

We know these places are trauma generating and yet a paper published just this year found that just under 50% of 44 admissions and discharges from two ATUS from February 2019 to March 2022 were delayed. The most prevalent reasons for discharge delays were identification of a new placement, recruitment of care staff and building work (Gibson et al 2023). Two young men close to me have been in and out of ATUs over the past decade. One is currently back in an ATU while the other has been waiting years for the local authority to sort out a home for him. Both families have been the driving force at extraordinary emotional, financial and physical cost to try to get their boys a life worth living.

This is apparently fine.

TEN. I was struck by Simon Jarrett mentioning at a conference just yesterday that the exclusion of people with learning disabilities during the industrial revolution when enormous institutions were built was arbitrary, as many people could have worked in factories. There is a direct and remarkably enduring line from then to now where we have people formally incarcerated in ATUs, or in versions of ATUs dressed up as supported living or residential homes where people don’t even know their neighbours and their neighbours don’t know them.

All our lives are impoverished by the exclusion of a proportion of the population, and the way in which we, as a society, are failing people is something we should all take responsibility for.

None of what we are talking about this evening is fine. None of it. Stop pretending it apparently is.

Thank you.